Warning: Long Gone Days, and this review, contain content and themes that may be distressing to certain audiences. Discretion is advised.

Long Gone Days is a game about war.

It is a game about the mental and physical toll war takes on those who participate in it, both by choice and by force. It is a game about being faced with unspeakable cruelty and striving to do the right thing even when subjected to faceless evil.

It is a game about those who fight, those who die, and those who are left behind.

I had committed a war crime about 30 minutes into the game, and it only took me that long because I did all the side quests beforehand.

Long Gone Days is still in early access, with a full release coming soon.

Breathe In, Aim

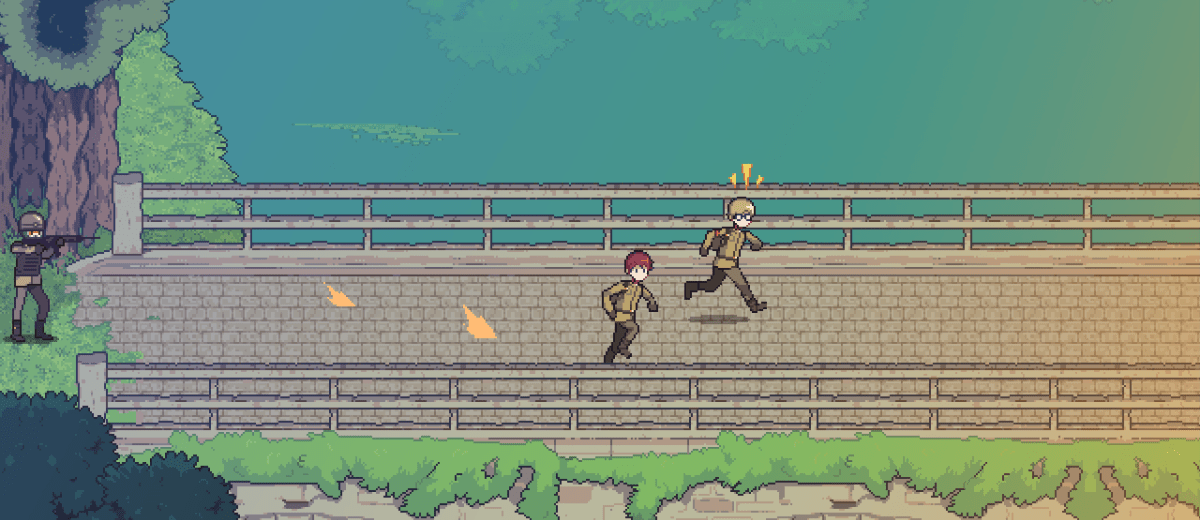

Long Gone Days is largely divided into two sections. First is active combat scenarios, and second is a more visual novel or adventure game style exploration section. You mostly engage in the latter of these two, with the combat scenarios being much shorter.

Combat in Long Gone Days is fairly standard turn-based RPG combat. You have a basic attack as well as a handful of skills with their own effects and some items you can use to restore your health as you take damage.

There are some interesting deviations from the norm, however. You can target specific points on enemies in order to affect your chance to hit them, how much damage you do, or even paralyze them, preventing them from acting for a turn. Deciding between damage that’s low but consistent versus the much greater damage inflicted by a rare headshot creates interesting tension in fights.

The other main gimmick is your morale. If your party is in good spirits, you deal more damage. But if you’ve lost the will to fight, you deal considerably less. Morale is also the resource you spend to use your skills.

Interestingly, one of the main party members is a non-combatant. He refuses to take up arms against his fellow man. (I’d appreciate it if he would shoot the unmanned drones, but I digress.) Instead, this character spends his turn giving a random state boost or small heal to a member of your party.

At the end of these battles, you are prompted to choose which reward you receive. Either items and equipment or a morale boost for the party. And this is a difficult choice. Because combat in Long Gone Days is brutal. Each individual battle is a chance for things to go very wrong. Healing during battle is generally inefficient, as your healing rarely outpaces the enemy’s damage output. Instead, using items out of combat between fights is more likely to get you through alive.

Also Read

Transmogrify PC Review: The Best Way To Defeat An Enemy

Transmogrify is a game with a strong central idea let down by a shoddy execution resulting in an experience that is…

Defy the Gods as a Witchy Moon Goddess in Hades 2

Supergiant announces Hades 2 for 2023 at the 2022 Game Awards. The sequel promises dark sorcery, witchery, and more frenetic roguelike…

The main character, Rourke, is a sniper. And thus, there are also sniper sections where you take enemies out from afar. These sections are usually very short, only a minute or so, and each shot is a one-hit kill. This is basically its own minigame instead of the normal combat.

But most of the time, you are not in combat. Most of the time, you are walking around a city or location, where you can speak with the locals and complete side quests.

What’s interesting about these sections is that there is no translation. If a character is speaking Russian, their dialogue will be in Russian. The same for German, or any other language. So if you want to be able to, say, read signs, talk to people, continue the story, or anything else that would feasibly require language, then you need to find a party member capable of translating the dialogue for you. And should your interpreter temporarily leave the party for whatever reason, you won’t be able to translate anything until they return.

During these sections, the party is limited to walking around and interacting with people and objects. Interacting with people provides dialogue, as you might expect, while items will have the player character internally monologue about that object.

It is these sections where all the side quests come from. At any time you can check your quest log for your current location, which will provide clues about where you need to go to start any side quests you haven’t found yet, as well as tracking your progress. These side quests are rarely difficult. Usually just running around and interacting with specific things. Some of them require you to track down scattered objects, or spot things in the environment that are slightly off in order to proceed.

Despite the simplicity of these sections, they are some of the most powerful moments in the game. Sure, from the description it doesn’t sound very interesting, but context makes this game shine. A fetch quest is far more interesting when what you’re fetching are stray animals so they can evacuate a town before the enemy army burns it to the ground, or when you’re hunting down newspapers so you have an idea of what’s happening in the outside world.

Breathe Out, Fire

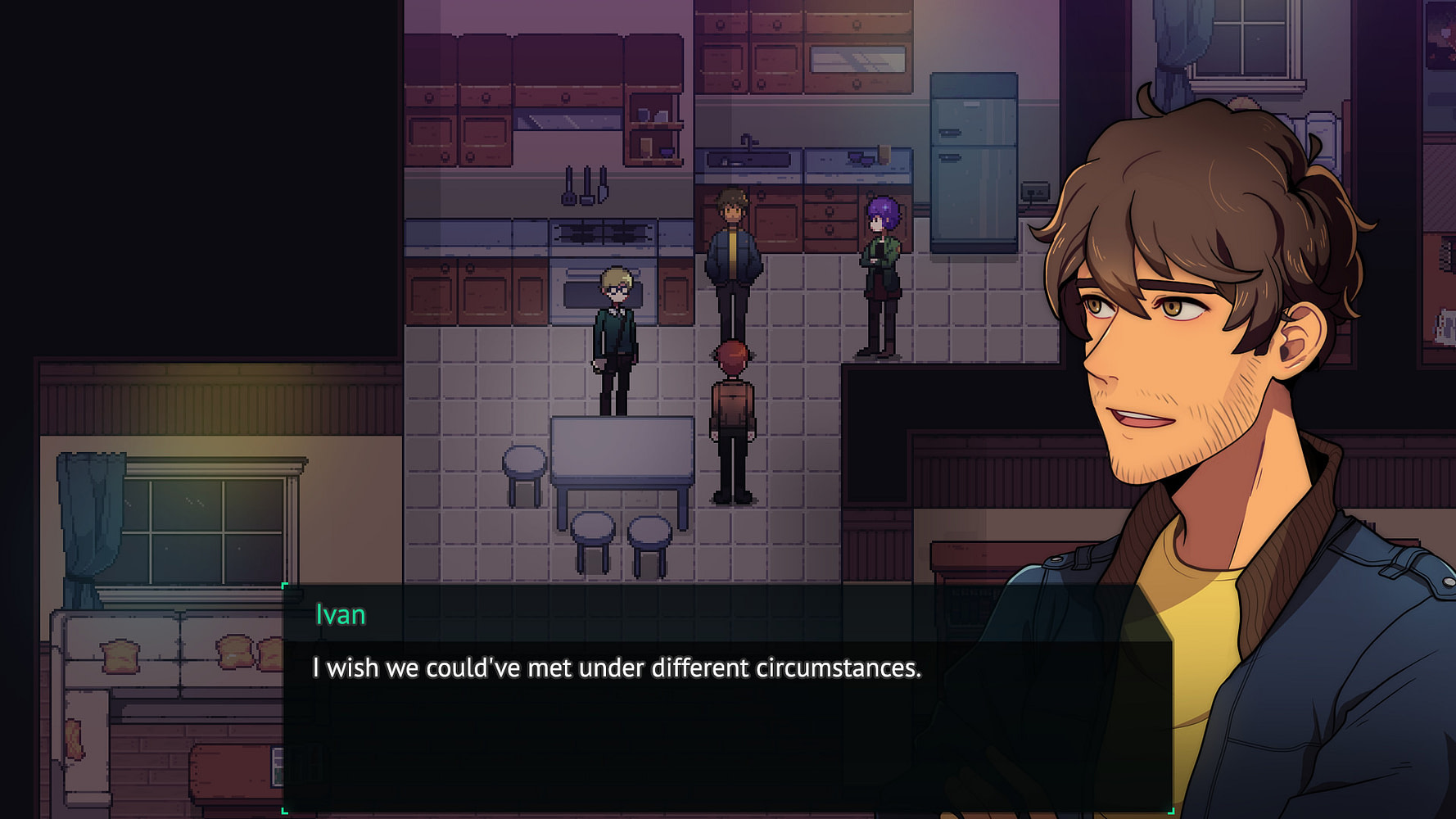

This game is visually stunning. The pixel art is incredibly detailed. Especially the environments, filled with some absolutely gorgeous foliage or with buildings complete with all the minutia that one might overlook, like old torn posters and graffiti.

The character sprites have some impressively fluid movements, and certain characters even have full on body language as they interact with the environment. How they sit, or use a computer, for example. Or how they cast shadows when moving in front of large windows. The characters even visibly breathe and blink.

And there are also the character portraits. Major characters have fully animated portraits that appear when they speak. These portraits have a number of different expressions and animations, like moving mouths and blinking. Frankly, it’s an impressive amount of additional detail for a character portrait to have just for something as simple as general dialogue.

The music is nothing to write home about, but it certainly isn’t bad. It sets the mood well and it’s composed well. There’s even a use of non-diegetic sound effects, like a clock chiming the hour. No, the music is not bad at all. But it’s nothing too impressive either, especially compared to the visuals. The sound effects are nice and crunchy.

Battles are represented by a pseudo first person perspective. The backgrounds are just as impressive fully drawn out instead of in the pixel art of the overworld. And enemies have superb animated full body images.

But this is a game about war. And there can be no story of war without the horrors that entails. I will not be fully addressing what happens in order to maintain the impact, but rest assured that this game delivers.

In Long Gone Days, Earth in the not to distant future has established a self-sustaining underground nation-state known as The Core. Not only does The Core provide everything for its citizens, but it has its own standing military. According to the Father General, this military defends humanity from threats to peace.

I’m sure I don’t have to tell you just how many cult-like vibes The Core gives off. Rourke hasn’t even seen the sun until the fateful mission that sets the game in motion. His opening narration on the nature of common sense as being something you learn certainly doesn’t help.

And during his first mission on the surface, Rourke learns a horrible truth about the nature of The Core and its military ambitions. This is unlikely to come as a surprise to the audience (indeed, the explanation is even in the trailer), but much of the drama is from Rourke’s inexperience with how things are on the surface. And so Rourke defects, convincing a medic to come with him. To defy orders and do what they can to help people instead of blindly obeying their superiors and committing atrocities.

It is a heavy story, of death and ambition, and the terrible cost of war. But it is not without its light moments. Indeed, if it was nothing but despair and gloom at all times, it would lose its impact. The downtime I mention as being what you spend most of the game doing—wandering around and talking to people—provides a beautiful insight to the world and the current state of affairs. And more importantly, to the characters themselves. The best moment of this is in Kiel, when you stay in a hostel, rooming with one of your party members, leading to a quiet bonding moment for them.

And there’s also drama outside of the party. The events of the story have shaken the lives of many people. The side quests usually involve you helping someone who have been placed in a difficult situation because of the recent attacks.

Conclusion

Long Gone Days has a lot to say about war and its physical and mental toll. None of it is new, but it is raw and real and just for that it’s worth looking into.

While the innovations on gameplay aren’t going to knock anyone’s socks off, it is an expertly crafted experience, and I eagerly await the release of the final chapter.