In June of 2019, Superliminal was announced. It’d been in development for several years prior and when the official announcement was made at E3 it suddenly came onto everyone’s radar. With a sleek, modern look and a fascinating gameplay gimmick, Superliminal was definitely one to keep an eye on. On release, however, it only seemed to last a couple of weeks in the ever-ephemeral social media zeitgeist before fading. Was this because the game was not good? I don’t think so, but I certainly don’t think it’s perfect, and I think I have a good idea as to why Superliminal hasn’t had the staying power everyone thought it would.

Wearing it’s inspiration on it’s sleeve, Superliminal tasks you as playing through an induced dream, where space and distance doesn’t behave like it does in the waking world. In this mind-bending puzzle game nothing is quite as it seems, and the exit signs don’t seem to point to the way out…

Size Matters (gameplay)

A few months before release, Superliminal delivered a couple of demos, these allowed players to experience the first couple of levels, and it really proved what the trailers had promised. The primary ‘resizing via perspective’ mechanic was intuitive and interesting, and was used in interesting ways. Players wondered, however, how this could evolve over the course of the entire game, especially when it felt like the thirty-minute demo had kind of covered all bases with what it was capable of.

Also Read

Transmogrify PC Review: The Best Way To Defeat An Enemy

Transmogrify is a game with a strong central idea let down by a shoddy execution resulting in an experience that is…

Defy the Gods as a Witchy Moon Goddess in Hades 2

Supergiant announces Hades 2 for 2023 at the 2022 Game Awards. The sequel promises dark sorcery, witchery, and more frenetic roguelike…

Thankfully, our worries were misguided, the final game is comprised of eight levels, each repeated several times throughout during which the game will either switch up how the primary puzzle mechanic is used, or it’ll switch to a new mechanic entirely. For instance, in one level the game turns out the lights, literally. You must navigate in the dark using minimal illumination and your ability to resize objects at will. This allows for a different approach to puzzle solving where you don’t need to create a way to progress, but simply find the way to move forward in the dark. Later in the game, you’re presented with some familiar objects at the start of a level, but instead of changing size when interacted with, they duplicate. The game does a fantastic job of quickly introducing you to new mechanics and getting you into the puzzles quickly without slowing its pace.

But, speaking of pacing, whilst the speed at which the game progresses feels perfect, when you realise you’re reaching the natural narrative climax it feels a little soon. And truly, coming in at about three hours to beat, Superliminal does leave the player wanting more. As the credits roll, It’s hard not to feel like some of the potential in this game wasn’t met. The main reason for this is that, as great as the variety is within this game, in a game this short, it ends up feeling like each mechanic doesn’t quite have it’s full options unlocked. For instance, the aforementioned light-based level almost borders on horror, but it’s not totally clear what the game is going for mechanically, other than just having exits to rooms that aren’t fully visible at first. The duplication mechanics are very interesting initially, but the game doesn’t find many ways to use the mechanic outside of simply duplicating things over the edges of different surfaces, which is a shame.

The gameplay focus for Superliminal is always clear, it’s about perspective. And it’s heavy inspiration from Antichamber shows from the get-go, but it separates itself with it’s looks and story. The thing is, those two things are also far from perfect.

Less is more (art)

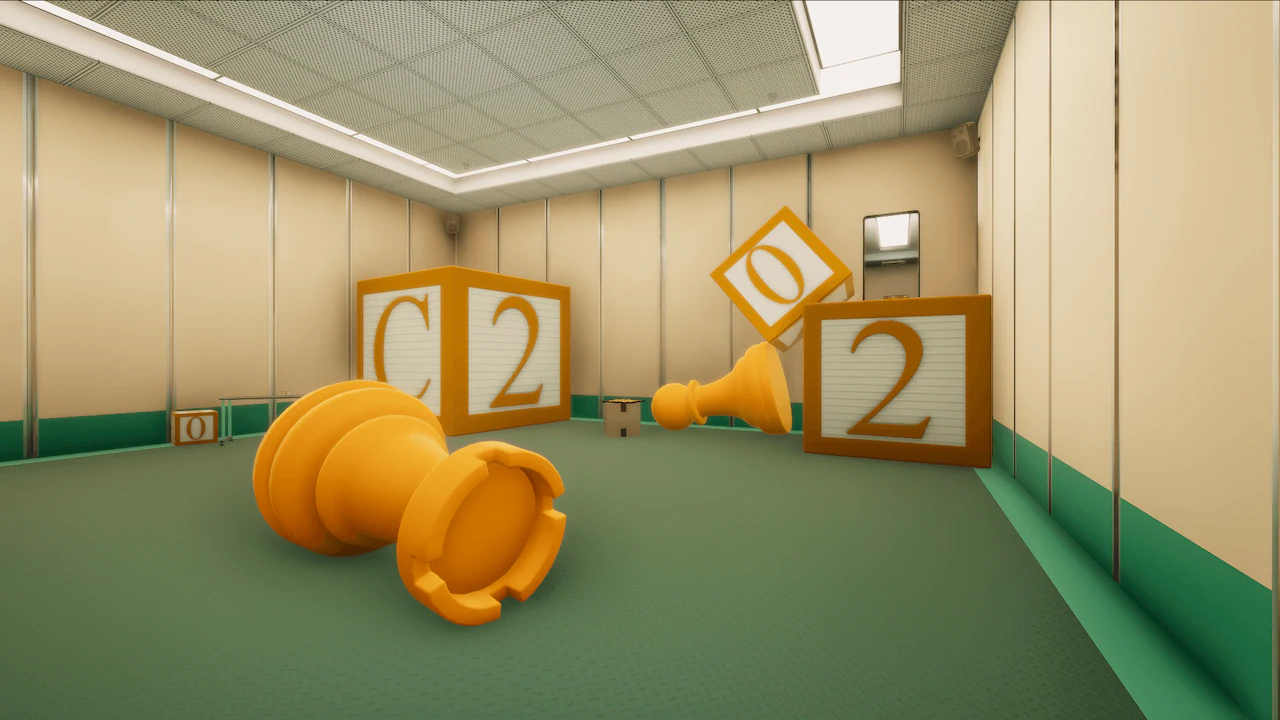

Imagine you’re sitting in a waiting room in an animated corporate PSA, that’s the look Superliminal has. Ok, that sounds really negative, but trust me it really works for this game. Whilst the gameplay heavily echoes Portal and, more heavily, Antichamber, the look of the game feels more taken from something like The Stanley Parable. The sleek, modern ‘waiting room’ aesthetic, like sitting in an office building made for a child, brings to life this liminal, dream-like world. The whole game takes place in a dream that has been expertly constructed to be soothing but still consummately professional. It’s very simple, and this is likely due to the small size of the team that worked on the game, ranging from six all the way down to just one person; the game’s creator, Albert Shih.

Many of the most interesting parts of this game’s design link very closely to the mechanics, particularly the perspective tricks and puzzles. One trick that will never get old whenever I see it in this game isn’t even a puzzle at all, it’s just a simple corridor, taking on the appearance of a long hall to a dead end, but is in fact a stretched out image that matches up perfectly to the player’s eyeline, hiding the way forward. It’s a simple and neat trick that is pulled off in a way that leaves the player feeling giddy with joy at being tricked.

The simple look also helps make the ‘backroom’ areas feel all the more out of place, with detailed brickwork and props lying around each room, it really feels like somewhere you shouldn’t be, like walking backstage during a play and seeing the peeling wallpaper and costume racks. As well as these backrooms, in the main areas the block colours and deceptively complex objects pull off the primary size-changing mechanic really well, every texture doesn’t pixelate or gain jagged edges when its size is changed, and no matter how much playing around you do with the objects in each scene, the game will do it’s best to not break. There are many times when this game feels more like a magic show than a videogame, the use of misdirection and other trickery is so fantastic that even when I’m trying to catch things like a flat picture of a row of lamp posts replace the actual row of lamp posts in front of me, I simply can’t catch it.

Nothing to sleep on (story)

Like with the art design and the gameplay, the story of Superliminal keeps its inspirations clear. The writing and dialogue immediately conjure up images of Wheatley from Portal 2, and the story itself could easily have you playing as one of the patients in 2015’s Nevermind.

I don’t want to say too much, as to not ruin how the story unfolds to the player, fittingly revealing what is happening currently and how you got into this dream-space to begin with as the game progresses, but I will give my thoughts on whether I think it was up to snuff.

Sadly, I’m a little underwhelmed with how I left this game. I attribute this, again, to the short length of the title, but the length isn’t the only issue I have with Superliminal’s Narrative. Whilst mostly unobtrusive, the plot often requires you to stand right next to tape players or radios just to keep up with what’s happening, which works at odds with the exciting and colourful puzzles. It urges you to continue forwards and see what it has to offer next, only to then pull you back and demand you stay put. And what do you hear when you’re listening to these scenes? The story, with shades of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, is one fraught with uncertainty and existentialism, but the game takes it’s writing style directly from portal 2, and in it’s attempt to inject humour into various moments during the game, sometimes comes off as unsure of itself. The humour in these moments feels out of place amongst the actual specifics of the story, which doesn’t treat well this game which is already sparse on plot to genin with. The story works well enough as a means of getting from one level to the next, but it’s poorly fleshed out, and sadly nothing to write home about.

Conclusion

Superliminal has creativity in spades, it also clearly has an understanding of physics and mathematics that would make my head hurt if someone tried to explain it to me. It has enough gameplay variety to keep you hooked for it’s entire runtime, but in all likelihood you’ll beat it in one sitting and end up feeling unfulfilled. Its puzzles are challenging enough, whilst still feeling fair and always satisfying to complete, but sadly the connecting plot thread that fills in the gaps between these puzzles is weak, and will likely lead to many quickly forgetting this game.

I look forward to the future of Pillow Castle, and the lead on this game, Albert Shih, who clearly has plenty of creativity and brains, but I wish this game’s campaign had more to offer from its three-hour runtime. It’s a game I’ll never forget playing, but I wish I’d been able to experience it more.